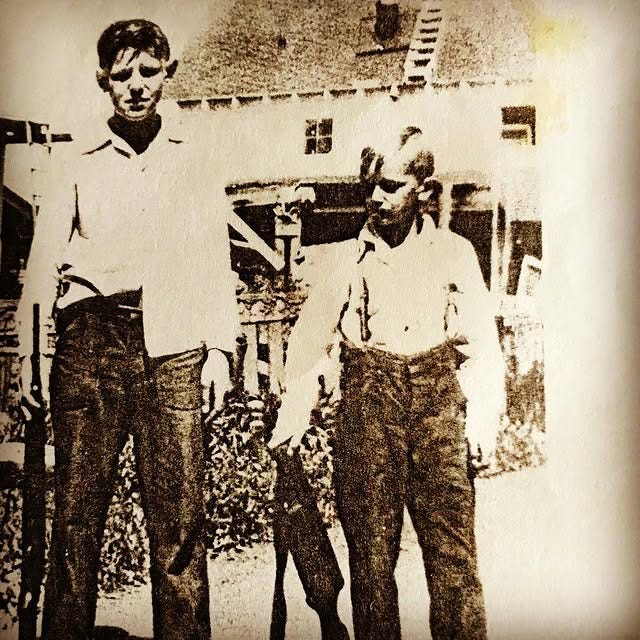

Pretty much everyone in Dad’s small town grew up knowing how to shoot a gun, and how to hunt. In the picture below, Dad was probably somewhere between twelve and fourteen. He’s the one on the left, with one of his little brothers.

So Dad grew up shooting, and hunting. But by the time I came around, I barely saw guns. I know we had a gun in the house, somewhere, in case we ever needed it to defend the family. But I never saw it. Dad also had a BB-gun that he used for target practice. But I never saw him kill anything with a gun.

Whenever Dad used the BB-gun I got the sense he absolutely knew how to hit what he was aiming at. But that was the extent of my exposure to guns. Throughout my entire childhood, he never went hunting or even fishing, even though he’d been part of commercial fishing crews for many years when he was younger. Even though he’d grown up hunting.

The dad I knew as a little kid was the guy who taught me to tell apart different kinds of trees, or who pushed our family to take long walks on the beach when we went camping, so everyone would come back to the campsite hungry and tired. Or who watched Carl Sagan’s Cosmos with me on PBS, totally enthralled.

Guns and hunting came up sometimes in the stories he would tell me about his early years living in Alaska. Most of these stories were about other people.

But one of them was about Dad and his favorite uncle.

In the thirties and forties, it was common for the people in Dad’s small community to hunt for food. To hear him tell it, during the last years of the Great Depression, World War II, and the years immediately following, hunting for food was the primary reason for hunting. But as times got better, and people had more disposable time and income, it became more common to hunt for sport.

And Alaska was teeming with game, endlessly, it seemed. Once, Dad told me how on commercial fishing trips, the water would seem to be boiling with fish, there were so many. He got a sad look on his face and said, “We thought it would last forever.” Then shrugged. “We were stupid.”

Southeast Alaska is an archipelago of hundreds of small islands, and, growing up there, Dad became familiar with the ins and outs of these islands by boat. Fishing and hunting was a way of life.

Dad’s real father was not in the picture, so he bonded with this uncle of his, who was the actual father figure in his life. On the day of this hunting story, Dad and his uncle loaded up a smaller fishing vessel with supplies for a hunting trip. The trip was for sport, and for the two of them to spend some time together.

They took the boat out to a favorite hunting spot. The aim: to hunt down a deer, kill it, and bring it home. As Dad explained, the ritual, once you got your deer, was to tie it to the mast of the boat and return back to town, triumphant hunters.

Dad and his uncle took the boat to the hunting spot, anchored it in shallower water, and set about their hunt. It was a beautiful fall day, Dad remembered. The sun hitting the trees just right. The air crisp, and smelling of the Earth and the surrounding water. A perfect day for a hunt.

Soon enough, they spotted their target: a deer. Dad and his uncle tracked it through the woods until they got to a point where they could take a clear shot. Dad’s uncle let him take the first one.

“I got a clean shot,” Dad said. (He probably told me exactly where his shot hit, but at this point in the story I was feeling so sad about the deer I have a feeling I blacked out that detail.)

Wherever he hit, the deer wasn’t dead instantly. Dad and his uncle went to it, to finish it off, if necessary, and to prepare it for transporting the carcass back to their boat.

“And when I knelt down by that deer,” Dad said, “it was still alive. I could see the life in its eyes. I saw it see me. And I knew I was looking at something that was just as alive as I was. And I hated that I had killed it. I hated it.”

But Dad went through the rest of the ritual. They made sure the deer was dead. They brought it back to the boat. They tied it to the mast, and came back to town, proudly displaying their kill for everyone to see.

Dad finished the story. “That was the last time I went hunting for sport,” he told me. “I understand it if you need the meat, if you need food. But killing something like that for sport…I just can’t do it anymore.”

I don’t know if this is a story Dad ever felt comfortable telling any of his male friends, or if he ever told the beloved uncle who accompanied him on this hunting trip. But I have always been proud of him for coming to this conclusion: that the life of an animal was just as valuable as his own life.

I think that’s what made him the kind of person who would tell me, matter of factly, that I never had to torture and kill another garden slug if I didn’t want to. It made him the kind of person who could honor the lives of the tiny, short-lived hamsters that I kept as pets in childhood.

Dad wasn’t perfect. He didn’t come from a perfect environment, and he wasn’t a perfect parent. But he understood that all life has value, and, over and over again, he imparted that understanding to me.

I’m proud of him for that. And I will always be grateful.